In about a week, there’s a DVOA meet at French Creek East. As you can imagine, I’m trying to get ready for it any way I can. The map they use for this venue is a different scale than I’m used to – most orienteering maps I’ve used are 1:10,000; last week’s map at Springton was 1:5,000. This map is 1:15,000. What that boils down to is that the map covers a lot more ground, so there’s a lot to look at, it looks very small comparatively, and it takes a longer time to get from one point to another on the map. Bring on the magnifier, baby.

While some orienteers don’t use magnifiers, some do; and not just with this scale map. Here’s what Sandy Fillebrown, one of my orienteering heroes, has to say about magnifiers: “I have one attached to my thumb compass that swings out of the way when I don’t need it. I always have it and use it when I can’t figure out what’s going on in the circle. I occasionally use it between controls when it seems important to understand a complex trail/stream/bridge/gorge crossing and I’ll use it in a sprint when the details of which side of what fence you need to be on is important or something like that. Many times I won’t use it at all in a race, and then there will be one when I need it several times – it just depends on the terrain.”

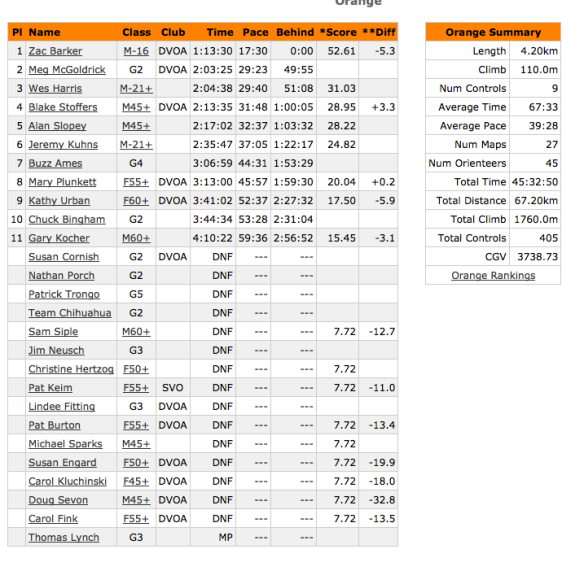

Well, this terrain calls for a magnifier, in my beginner’s opinion. Everything seems so…tiny and subtle. So the other day, I borrowed my Dad’s magnifier, and went out to French Creek East to try and wrap my head around the map, and see what the terrain was like. I attempted a DVOA Orange course from 4/2006; and with not much luck, actually. My goal was to just go slow and get as many controls (features in this case) as I could. Instead, I found myself wondering where I was a lot of the time that I was off-trail. The scale is a big adjustment to make, when usually you walk 20 paces for 80m; here you walk 30 paces for 80m, and so on. And it seemed to me there wasn’t a lot to see, or rather, there wasn’t a lot to see that I’m used to navigating with. I got really nervous out there, actually, and that was discouraging. So then I just decided to stay on trails and see as much as I could; maintain contact with the map; identify what I could. I ended up going 5 miles in about 2 hours…session data here. A little ankle twist added to my downcast mood.

I got number 1 after a bit. Number 2, I misidentified at first, being farther south than I needed to. Number 3, I got really uncomfortable off-trail and went all the way to a trail to get.

Feeling really down about myself, (though it had been a beautiful day, and I know I’m seriously lucky to be on this planet, doing the things I want to,) I got home and did the usual logging on Attackpoint. Later in the afternoon I was delighted to find some really nice notes from Sandy, my brother, and Speedy about FCE…and how I’ve turned “hard-core.” I’m hardly hard-core guys, but it was good to hear that that others find the scale difficult, or have had a bad time there despite being really really good at orienteering.

Speaking of hard-core, I had a funny encounter towards the end of my training session. I spoke briefly with one of the workers clearing trails of downed branches after the forest fires. As I went running away, she said, “thank you for your service.” Couldn’t for the life of me figure out what she meant until I got back to my car and took off my hat – the Marines hat that I consider my ‘lucky hat’ that was too small for my Dad, the actual Marine. So, she thought I was a Marine. Boy was she way off! If only she knew my inner thoughts about how icky the bugs were.

Today, I stumbled on a great DVOA article by Eric Weyman on orienteering at French Creek:

- “On the ground, the terrain is characterized by the lack of obvious, recognizable features. While there is a near absence of medium-sized features, there is an abundance of small and subtle features; some would say that there is an abundance of “non-existent” features as well.

- However, to orienteer well here, one must learn to recognize and even rely on many features that in other terrains are insignificant or unmapped.”

I guess that’s why Speedy, another orienteering hero, says this about the terrain at FC: “I believe FC terrain is the best we have in close proximity to Philadelphia from a technical aspect of orienteering.”

Okay, I get it. This is a place to really improve my skills. My brother wants to do some contour training with me, and is making me a little course to do with just contours, no other features. At first I thought this idea was a mistake, too advanced for me, I’m not ready for that type of thing. But I think differently after reading more from the Weyman article:

- “The ripples are not the work of a nervous draftsman, but in fact accurately reflect the many subtle spurs and reentrants in the terrain. In addition, the spacing of the contours is also worth noting since they accurately depict changes in slope that are often more apparent in the terrain than on the map and are a very useful feature that most orienteers are not accustomed to using.”

I looked back in the annals of DVOA Orange course results: there are many many many DNFs in Orange over the years. Why is it so hard to set an intermediate course here? The answer, in Eric Weyman’s aforementioned article:

- “French Creek terrain provides typical beginner’s level orienteering, utilizing the trail network, a couple streams and the nearby point features. However, once the orienteer leaves the security of the linear features, the difficulty switches almost immediately to the advanced level.

- So what does the Orange (intermediate) level orienteer have to look at? Probably the most usable feature is the stony ground, which often occurs in large, distinct pieces and functions as an area feature comparable to fields and marshes in other terrains. Even when the stony ground is complex in its outline, it can still be generalized into a usable area feature. To a lesser extent, areas of green (thick vegetation) can be generalized in the same way.

- In addition, there are some intermediate-sized contour features that might not be obvious on the map but are recognizable in the terrain. One example is a multi-contour hillside that is noticeably steeper than the slopes above and below. Usually accompanying these steeper pitches is a “shoulder” at the top edge of the slope where it levels off and a “bench” on the lower side of the slope where it levels off before dropping off further below. For all of these features, it is important to pay attention to the spacing of the contours, which is a skill most orienteers rarely apply.

- There are more common intermediate-level contour features such as ridges, valleys and hilltops that are mostly large, broad and can be counted on two hands to cover the whole map. Nevertheless, they can’t be ignored because there really aren’t many other intermediate-sized features.”

“Many first timers to French Creek comment that there are many details on the map but nothing to see in the terrain. It usually takes a return trip or two to realize that not only are the details all there, but they are precisely mapped, and, once the orienteer makes some adjustments, navigation is in fact possible.”

Rock on!

Other points from article I want to think about:

- “The intermediate courses frequently require crossing through sections of terrain that only have advanced-level point features on the map. Therefore, accurate use of rough-compass technique is important to get to the linear or area collecting feature on the other side.

- “Aiming off” is the compass technique of intentionally going to one side of the direct line in order to hit a collecting feature on the intended side, then proceeding along that feature in order to find the control or an attack point before moving on. This is used in situations where the likelihood of finding the objective by direct bearing is low and not worth the risk of missing it. At French Creek this applies almost everywhere, since there are few obvious supporting features.

- Contour Reading: Though few intermediate-level contour features-such as valleys, ridges and hills-exist, the ones that are there are rather easy to recognize and must be utilized. While noting these shapes, you should also be aware of the direction of your travel relative to the contours, whether it is directly uphill or downhill, or at an angle to the slope of the hill, or directly along the slope, contouring along the hillside. Paying attention to the direction you want to travel relative to the slope, especially when used with rough compass, can be an effective combination.

- Attack Points: Of course, attack points are important on all levels of courses, but for intermediate-level competitors the application is simpler. Almost every reasonable Yellow and Orange level attack point will be right along a linear feature, usually a trail, but sometimes a stream or clearing. My advice can be boiled down to one rule: don’t leave a linear feature without first finding a sure attack point. One warning: often very similar features lie along the linear feature, such as bends, junctions, rocks, terraces, rootstocks, etc., so it is usually worth taking some extra time to check multiple confirming features before staking your attack. When carefully designed, French Creek Yellow and Orange courses aren’t necessarily difficult. In fact, there are probably more than the usual number of easy legs if the course setter properly errs on the conservative side when there aren’t appropriately difficult features. Usually the “O” problem is very straightforward: rough compass through the featureless hillside to the next linear feature, find a known point and repeat. This pattern and the other intermediate-level concepts certainly underlie the advanced-level orienteering as well, with a few more complexities thrown in.

- Route Choice: French Creek can present route-choice problems. Legs here often involve the classic, “straight through the forest” vs. “around on the trail” decision. The contour [around] vs. climb situation appears less frequently because the gradual slopes present few climbs worth avoiding. The more frequent dilemma is the navigation-oriented route choice. Most respected orienteers advise that you base your route-choice decisions on ease of navigation, especially the risk involved in the final approach to the control. In no other terrain is this idea more important. Often at French Creek supporting features dictate only one or two reasonable approaches. It is a common practice to run wide off the straight line for the sole purpose of finding a handrail or a series of features that can be relied upon. Such a technical route choice accepts a known small time loss because of the longer route, over the possibility of a large time loss due to error with a straight-line route. It is one which many orienteers have never considered or applied but is critical to successful orienteering at French Creek.”

More on FCE later – I’m planning on returning there sometime early next week. I’m hoping to successfully identify more than one or two charcoal terraces, as they seem to be an abundant feature, and could be very helpful out there in the subtle terrain. I really wish I had read this article before I went! (And I hope that the course setter for the upcoming meet reads it.)